Diver's Guide to the Ear

Scott Hagen Dec 17, 2019

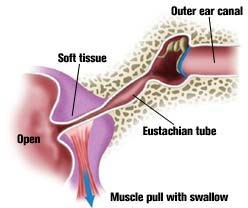

Listen up - Those flaps on either side of your head do more than hold your sunglasses in place. Protect the delicate inner workings of your ears with practical advice from the experts. From simple cases of swimmer's ear to the serious and sometimes lasting damage of barotrauma, divers are vulnerable to ear problems because the delicate mechanisms that govern our hearing and balance just aren't designed for the rapid pressure changes that result from diving. Fortunately, ear injuries are preventable. All Things Being Equal... Your middle ears are dead air spaces, connected to the outer world only by the Eustachian tubes running to the back of your throat. If you fail to increase the pressure in your middle ears to match the pressure in your outer and inner ears, the result is painful middle-ear barotrauma, the most common pressure-related ear injury. The key to safe equalizing is opening the normally closed Eustachian tubes. Each has a kind of one-way valve at its lower end called the "Eustachian cushion," which prevents contaminants in your nose from migrating up to your middle ears. Opening the tubes, to allow higher-pressure air from your throat to enter your middle ears, normally requires a conscious act.  Swallowing usually does it. In fact, you equalize your ears many times a day without realizing it, by swallowing. Oxygen is constantly absorbed by the tissues of your middle ear, lowering the air pressure in those spaces. When you swallow, your soft palate muscles pull your Eustachian tubes open, allowing air to rush from your throat to your middle ears and equalize the pressure. That's the faint "pop" or "click" you hear about every other swallow. Scuba diving, however, subjects this equalization system to much greater and faster pressure changes than it's designed to handle. You need to give it help.

Swallowing usually does it. In fact, you equalize your ears many times a day without realizing it, by swallowing. Oxygen is constantly absorbed by the tissues of your middle ear, lowering the air pressure in those spaces. When you swallow, your soft palate muscles pull your Eustachian tubes open, allowing air to rush from your throat to your middle ears and equalize the pressure. That's the faint "pop" or "click" you hear about every other swallow. Scuba diving, however, subjects this equalization system to much greater and faster pressure changes than it's designed to handle. You need to give it help.

Why You Must Equalize If you dive without equalizing your ears, you can experience painful and damaging middle-ear barotrauma. Step-by-step, here's what happens: • At one foot below the surface Water pressure against the outside of your eardrums is 0.445 psi more than on the surface air pressure on the inside. They flex inward and you feel pressure in your ears. • At four feet the pressure difference increases to 1.78 psi. Your eardrums bulge into your middle ears. So do the "round windows" and "oval windows" between your middle and inner ears. Mucus begins to fill your Eustachian tubes, making it difficult to equalize your ears if you try. Nerve endings in your eardrum are stretched. You begin to feel pain. • At six feet 2.67 psi difference. Your eardrum stretches further. Its tissues begin to tear, causing inflammation that will last up to a week. Small blood vessels in your eardrums may expand or break, causing bruising which will last up to three weeks. Your Eustachian tubes are now locked shut by pressure, making equalization impossible. Pain increases. • At eight feet 3.56 psi difference. If you are lucky, blood and mucus is sucked from surrounding tissues and begins to fill your middle ear. This is called middle-ear barotrauma. Fluid, not air, now equalizes pressure on your eardrums. Pain subsides, replaced by a feeling of fullness in your ears which will remain for a week or more until the fluid is reabsorbed by your body. • At 10 feet 4.45 psi difference. If you aren't so lucky—if your descent is very fast, for example—your eardrums may break. Water will flood your middle ear. The sudden sensation of cold against your balance mechanism, your vestibular canals, may cause vertigo, especially if only one eardrum breaks. Suddenly, the world is spinning around you, though the sensation will probably stop when your body warms up the water in your middle ear. Or, if you try to equalize by blowing hard and long against pinched nostrils, you may rupture the "round window" membrane between your middle and inner ears. This is called inner- ear barotrauma. Perilymph fluid drains from the cochlea into the middle ear. Temporary, even permanent, hearing loss may result.

How To Equalize All methods for equalizing your ears are simply ways to open the lower ends of your Eustachian tubes, so air can enter. • Valsalva Maneuver. This is the method most divers learn: Pinch your nostrils (or close them against your mask skirt) and blow through your nose. The resulting overpressure in your throat usually forces air up your Eustachian tubes. But the Valsalva maneuver has three problems: It does not activate muscles which open the Eustachian tubes, so it may not work if the tubes are already locked by a pressure differential (see illustrations). It's all too easy to blow hard enough to damage something. And blowing against a blocked nose raises your internal fluid pressure, including the fluid pressure in your inner ear, which may rupture your "round windows." So don't blow too hard, and don't maintain pressure for more than five seconds. Other methods, some safer, include: • Toynbee Maneuver. With your nostrils pinched or blocked against your mask skirt, swallow. Swallowing pulls open your Eustachian tubes while the movement of your tongue, with your nose closed, compresses air against them. • Lowry Technique. A combination of Valsalva and Toynbee: while closing your nostrils, blow and swallow at the same time. • Edmonds Technique. While tensing the soft palate (the soft tissue at the back of the roof of your mouth) and throat muscles and pushing the jaw forward and down, do a Valsalva maneuver. • Frenzel Maneuver. Close your nostrils, and close the back of your throat as if straining to lift a weight. Then make the sound of the letter "K." This forces the back of your tongue upward, compressing air against the openings of your Eustachian tubes. • Voluntary Tubal Opening. Tense the muscles of the soft palate and the throat while pushing the jaw forward and down as if starting to yawn. These muscles pull the Eustachian tubes open. This requires a lot of practice, but some divers can learn to control those muscles and hold their tubes open for continuous equalization.

• Valsalva Maneuver. This is the method most divers learn: Pinch your nostrils (or close them against your mask skirt) and blow through your nose. The resulting overpressure in your throat usually forces air up your Eustachian tubes. But the Valsalva maneuver has three problems: It does not activate muscles which open the Eustachian tubes, so it may not work if the tubes are already locked by a pressure differential (see illustrations). It's all too easy to blow hard enough to damage something. And blowing against a blocked nose raises your internal fluid pressure, including the fluid pressure in your inner ear, which may rupture your "round windows." So don't blow too hard, and don't maintain pressure for more than five seconds. Other methods, some safer, include: • Toynbee Maneuver. With your nostrils pinched or blocked against your mask skirt, swallow. Swallowing pulls open your Eustachian tubes while the movement of your tongue, with your nose closed, compresses air against them. • Lowry Technique. A combination of Valsalva and Toynbee: while closing your nostrils, blow and swallow at the same time. • Edmonds Technique. While tensing the soft palate (the soft tissue at the back of the roof of your mouth) and throat muscles and pushing the jaw forward and down, do a Valsalva maneuver. • Frenzel Maneuver. Close your nostrils, and close the back of your throat as if straining to lift a weight. Then make the sound of the letter "K." This forces the back of your tongue upward, compressing air against the openings of your Eustachian tubes. • Voluntary Tubal Opening. Tense the muscles of the soft palate and the throat while pushing the jaw forward and down as if starting to yawn. These muscles pull the Eustachian tubes open. This requires a lot of practice, but some divers can learn to control those muscles and hold their tubes open for continuous equalization.

Practice Makes Perfect Divers who experience difficulty equalizing may find it helpful to master several techniques. Many are difficult until practiced repeatedly, but this is one scuba skill you can practice anywhere. Try practicing in front of a mirror so you can watch your throat muscles.

When To Equalize Sooner, and more often, than you might think. Most authorities recommend equalizing every two feet of descent. At a fairly slow descent rate of 60 feet per minute, that's an equalization every two seconds. Many divers descend much faster and should be equalizing constantly. The good news: as you go deeper, you'll have to equalize less often—another result of Boyle's Law. For example, a descent of six feet from the surface will compress your middle ear space by 20 percent and produce pain. But from 30 feet you'd have to descend another 12.5 feet to get the same 20 percent compression. When you reach your maximum depth, equalize again. Though the negative pressure in your middle ear may be so small that you don't feel it, if it's maintained over several minutes it can gradually cause barotrauma.

Tips For Easy Equalizing 1. Listen for the "pop." Before you even board the boat, make sure that when you swallow you hear a "pop" or "click" in both ears. This tells you both Eustachian tubes are open. 2. Start early. Several hours before your dive, begin gently equalizing your ears every few minutes. "This has great value and is said to help reduce the chances of a block early on descent," says Dr. Ernest S. Campbell, webmaster of "Diving Medicine Online" (see: www.gulftel.com /~scubadoc/entprobs.html). "Chewing gum between dives seems to help," adds Dr. Campbell. 3. Equalize at the surface. "Pre-pressurizing" at the surface helps get you past the critical first few feet of descent, where you're often busy with dumping your BC and clearing your mask. It may also inflate your Eustachian tubes so they are slightly bigger. Many authorities recommend this, but some disagree. Dr. Murray Grossan, another diving doc and webmaster (see: www.ent-consult.com/referralindex.html), says, "Equalizing on the surface should not be done. Only inflate when you need to. Pre-pressurizing is not beneficial." Most of us find it does, in fact, help. The lesson here is to pre-pressurize only if it seems to help you, and to pressurize gently. 4. Descend feet first. Air tends to rise up your Eustachian tubes, and fluid-like mucus tends to drain downward. Studies have shown a Valsalva maneuver requires 50 percent more force when you're in a head-down position than head-up. 5. Look up. Extending your neck tends to open your Eustachian tubes. 6. Use a descent line. Pulling yourself down an anchor or mooring line helps control your descent rate more accurately. Without a line, your descent rate will probably accelerate much more than you realize. A line also helps you stop your descent quickly if you feel pressure, before barotrauma has a chance to occur. 7. Stay ahead. Equalize often, trying to maintain a slight positive pressure in your middle ears. 8. Stop if it hurts. Don't try to push through pain. Your Eustachian tubes are probably locked shut by pressure differential, and the only result will be barotrauma. If your ears begin to hurt, ascend a few feet and try equalizing again. 9. Avoid milk. Some foods can increase your mucus production. Dairy products can cause a fourfold increase. 10. Avoid tobacco and alcohol. Both tobacco smoke and alcohol irritate your mucus membranes, promoting more mucus that can block your Eustachian tubes. 11. Keep your mask clear. Water up your nose can irritate your mucus membranes, which then produce more of the stuff that clogs.

Other Ear Problems Middle-Ear Barotrauma on Ascent, or Reverse Squeeze What happens: Pressure must be released from your middle ear as you ascend, or the expanding air will bulge and even break your eardrums. Normally, expanding air escapes down your Eustachian tubes, but if the tubes are blocked with mucus at depth (usually the result of poor equalizing on descent, diving with a cold or relying on decongestants that wear off at depth), barotrauma can result. What you feel: Pressure, then pain. Some divers also feel vertigo from the unusual pressure on their balance mechanism. What to do: Sometimes one of the equalizing techniques used on descent will clear your ears on ascent. Pointing the affected ear toward the bottom may help, too. Ascend as slowly as your air supply allows, remembering that the last 30 feet will be most difficult. Otherwise, you will just have to endure the pain to reach the surface.

Inner-Ear Barotrauma What happens: Sometimes, the stresses on your middle ear—from not equalizing or from trying too hard with a Valsalva technique—damage the adjacent inner ear hearing structures (the cochlea) and balance structures (the vestibular canals), and permanent incapacity can result. What you feel: o Deafness: Hearing loss can be complete, instant and permanent, but divers usually lose just the higher frequencies. The loss becomes noticeable only after a few hours. You may not be aware of the loss until you have a hearing test. o Ringing: You may experience "tinnitus," a ringing or hissing in your ears. o Vertigo: The sense that the world is whirling around you, often accompanied by nausea. What to do: Abort the dive and go as soon as possible to an ear, nose and throat specialist with experience treating divers. Inner-ear injuries are tricky and require prompt, correct treatment from a specialist. Outer-Ear Barotrauma What happens: If your ear canal is blocked by a tight hood, a glob of wax or a non- vented ear plug, it becomes another dead air space that can't equalize on descent. Your eardrum bulges outward, and increasing pressure in the surrounding tissues fills the canal with blood and fluid. What it feels like: Similar to middle-ear barotrauma. What to do: Keep your outer ear clear, which can be difficult for divers with exospores (see pg. 94). These are hard, bony growths in the ear canal that can trap dirt and wax and even grow so big they completely block the ear canal. They are believed to be caused by repeated contact with cold water. Prevention: Wear a hood. It will reduce the flow of water to your ears, and what does reach them will be warmer.

Can You Bend Your Ears? Yep. It's called inner-ear DCS (decompression sickness) and happens when micro bubbles form in the fluid-filled spaces of the inner ear, the cochlea and vestibular canals, following decompression. Symptoms are deafness, vertigo and tinnitus not attributable to barotrauma damage, and can occur without signs of central nervous system DCS, such as tingling and joint pain. Bottom line: If you've pushed the limits, be alert for inner-ear symptoms and go immediately to a specialist if you experience any problems. Barotrauma damage and DCS damage to the inner ear have similar symptoms, but the treatment is very different. Recompression, which helps when the cause is DCS, can make the problem worse when the cause is barotrauma. Can You Dive With Barotrauma? OK, you screwed up on your first dive of your vacation, didn't listen to the pain in your ears, and now you've got middle-ear barotrauma. Your ears feel "full" (they are: with blood and mucus) and you can't hear too well. But you feel fine, and equalizing is no longer a problem. Can you continue to dive for the rest of the week you paid so much for? Some divers do, but they are taking a serious risk of permanent loss of hearing or, even worse, balance control. In addition to the obvious risk of infection, remember that you can't be sure you haven't also damaged your inner ear at the same time. Symptoms of the latter aren't always strong or immediate. All the medical advice says that if you've suffered middle-ear barotrauma, get out of the water and stay out until it clears up. Vertigo: Which Way Is Up? It feels exactly like way too many beers, and often leads to the same nausea. Unfortunately, this case of the "whir lies" probably won't be gone in the morning. Vertigo, the sense that the world is spinning around you, is a common symptom of middle-ear or inner-ear injury. That's because your balance mechanisms, called the vestibular canals, are located adjacent to both ear spaces. In fact, they're considered part of your inner ears, and separated from the cochlea (the hearing structures) by the thinnest membranes in your body—two cells thick. If vertigo happens under water, you may not be able to tell which way is up and panic. (Emergency tip: watch the water in your mask to judge your orientation and follow your bubbles, slowly, to the surface.) Damage to your vestibular canals, whether by DCS or by pressure shock, is usually permanent. Vertigo may go away in two to six weeks because your brain learns to compensate and ignores the side that's damaged, but the canal will not heal. Damage the vestibular canals on the other side too, and you could be unable to drive a car, much less dive. Vertigo can also occur from stimulation of one side and not the other—the pressure difference if only one ear equalizes or the temperature difference if cold water enters one ear but not the other. In both cases, your brain interprets unequal stimulation of your vestibular systems as movement. This type of vertigo disappears with the unequal stimulation, fortunately, and leaves no after-effects.